A Submarine Chaser

I’ve always loved the sea. The vastness of it… The wonder of what lies on the other side… It was only natural that in Law School, I found myself pursuing a specialty in Admiralty and Maritime Law. Like Michael Bluth, dreaming of becoming a “Submarine Chaser…”

In reality, most of Admiralty Law is incredibly boring – unless you’re really into complex jurisdictional chess games. The Costa Concordia and other interesting cases are few and far between. Cases typically consist of arguing that one court has jurisdiction over another. A diminishing number of cases even make it to court, because most cases are now decided in arbitration.

As a field, admiralty is one of the most esoteric in the legal profession. Many practitioners obtain an advanced law degree (LLM) to learn the complexities of admiralty law. My first encounter with the field was as a member of the Maritime Law Bulletin (MALABU). For two years, I reviewed developments in admiralty law and edited articles for publication. As a 3L, I was selected to represent the school in the John R. Brown Admiralty Moot Court Competition. I was thrilled to be going, but the pit in my stomach grew as I contemplated arguing against the nation’s top legal minds.

Here’s how the competition works: there’s a hypothetical problem released in mid-December and all teams have about a month to write a petition for certiorari. To my new wife’s chagrin, I spent much of our Caribbean cruise buried in Schoenbaum’s Treatise on Admiralty (but where better to study admiralty than aboard a massive ship?). The case involved a casino boat called the Lucky Star and an employee, Pauline Parker. The employee was severely injured while aboard the ship, and the amount she could recovered varied based on whether State or Federal was applied. Since “Vessels” are within the ambit of Federal Admiralty jurisdiction, the case turned on whether a riverboat casino constitutes a “vessel” under 1 U.S.C. § 3. The craft at issue was readily capable of navigation; however, it had been moored to a dock for years and received utilities from the shore. If the Lucky Star was determined to be a vessel, the case would fall within federal maritime jurisdiction and crew members would be entitled to tort relief under the Jones Act, 46 U.S.C. § 30104.

Knowing that the question writers often modeled the hypothetical on an upcoming issue for the court, I was determined to find this case. Eventually, I found the proverbial needle in a haystack. The real case, Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach was awaiting certiorari out of the 11th Circuit. Borrowing heavily from Lozman’s petition for cert., my partner and I hammered away at our brief. After multiple sleepless nights, we finished our 40-something page brief in the 11th hour and overnighted it to New Orleans where it would be distributed for scoring.

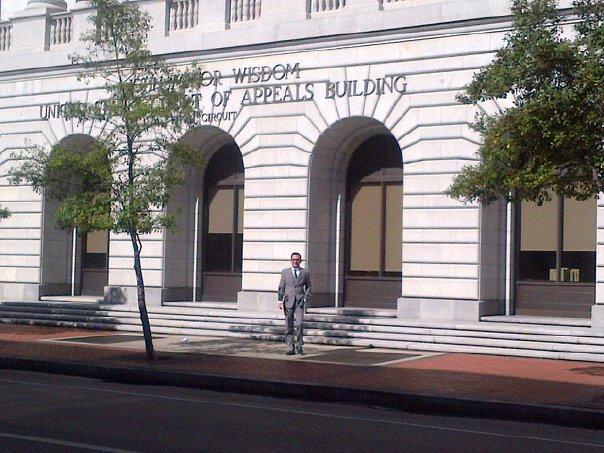

We practiced oral arguments relentlessly for the next month before heading to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans. I rehearsed my argument maniacally: in the shower, while driving, in my sleep… In each round, I would be arguing before a panel of 3 judges. Each student would have to argue “on” and “off” brief (each round arguing a different side of the case), so it was crucial to know both sides of the case. I knew that the pool of judges consisted of admiralty attorneys and actual 5th Circuit Judges. The idea that these practitioners had 30+ years of admiralty experience motivated me to learn everything I possibly could. I dredged Westlaw and LexisNexis for the most obscure admiralty cases of the last two centuries. I read books on oral argument and persuasion. I read everything Google returned for the search, “oral argument tips.” When I got on the plane for New Orleans, I knew an obscene amount of information about what constitutes a “vessel.”

After 3 rounds of oral argument, I learned that my team would not be advancing to the semi-finals. During the award ceremony on the final night, we received our score sheets. Upon reviewing my scores, I discovered that my score had been miscalculated during an earlier round. After many emails and much number crunching, I came in second place. My score was two-tenths of a point off the first place finisher. There is even more to the story, which I will not belabor you with now. Regardless, I was more than happy to have placed second out of 50 contenders from the nation’s top law schools.

Upon returning home, I continued to follow Lozaman v. City of Riviera Beach. The Supreme Court had granted certiorari and the parties would be making oral arguments soon. After getting home, I wrote an article exploring the fate of moored “vessels” and implications of the Lozman decision. Drawing from my undergraduate training in economics, I provided suggestions for an optimal “vessel” classification system. Months later, it turned out that the Supreme Court’s decision was based on a similar rationale (see Full Opinion Here).